Marie Bracquemond

Marie Bracquemond (1840–1916) was one of the “three great ladies” of Impressionism, a brilliant painter sidelined by her jealous husband and misogynistic art circles. Her story is a feminist cautionary tale of talent stifled by marriage to a controlling artist, later revived by 20th-century women’s art history.

Daughter of a Modest Family

Born December 1, 1840, as Marie Anne Caroline Quivoron to a struggling family raised mostly by her mother after her parents’ separation. As a teenager, she studied drawing in Étampes, where local teachers quickly spotted her prodigious talent.

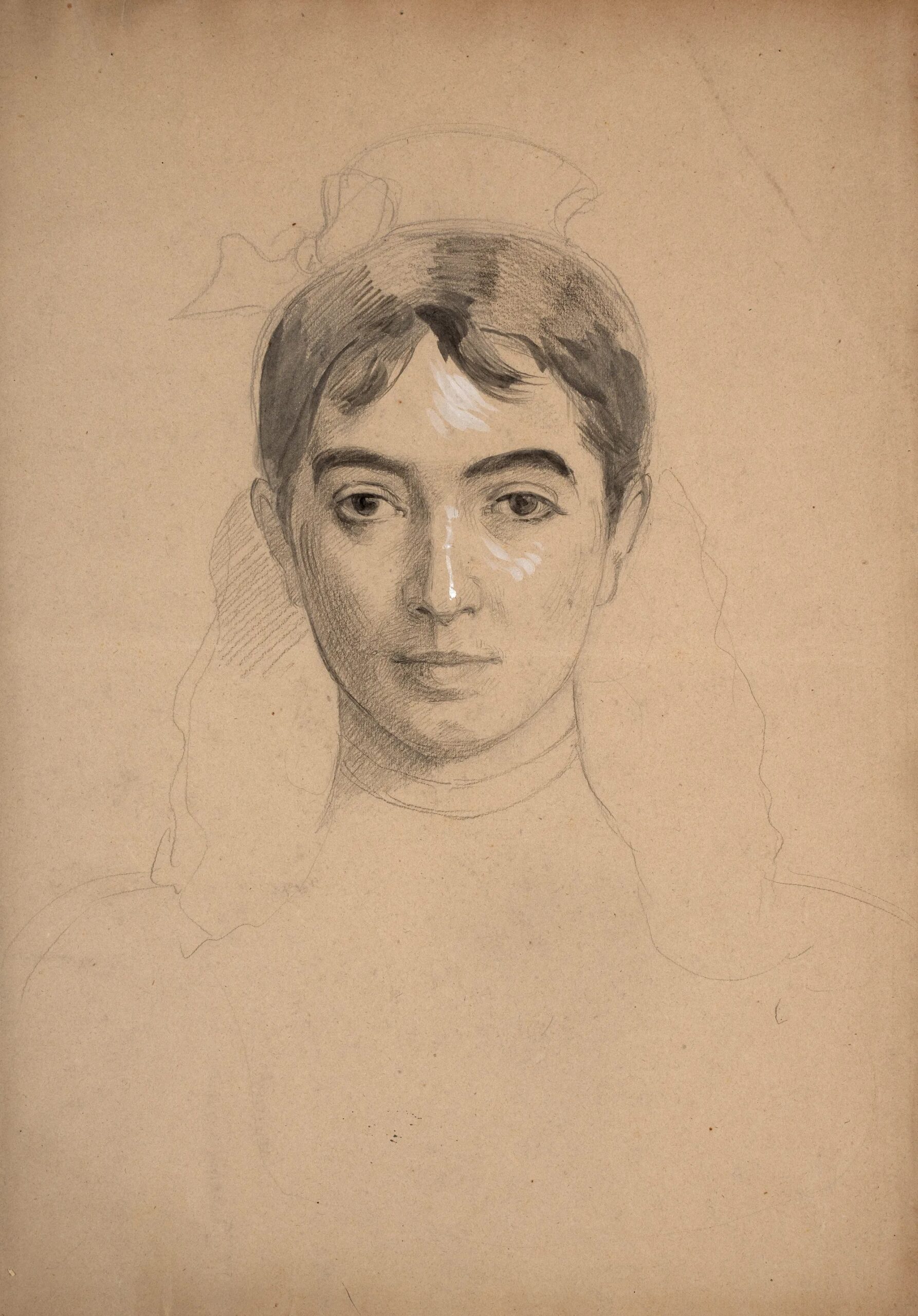

From Ingres’s Pupil to Louvre Copyist

Young Marie received advice from Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres himself, who urged her toward “safe” feminine subjects: flowers, fruit, portraits. Admitted to the Salon from 1857, she earned a state commission copying Old Masters at the Louvre – there Félix Bracquemond first saw her.

Marriage to Félix Bracquemond

In 1869, after two years’ courtship, she married renowned engraver Félix Bracquemond despite her mother’s objections. Their union promised artistic partnership but devolved into conflict: Félix adored Japonisme and Old Masters while scorning the Impressionism where his wife shone.

Designing Ceramics for Haviland

Through Félix, Marie joined Atelier d’Auteuil, designing ceramics for Haviland & Co. in Limoges. She created plates, services, and the monumental ceramic panel “The Muses” shown at the 1878 World’s Fair – impressive work now rarely linked to her name.

Shift from Academic Realism to Impressionism

Her early works leaned academic, closer to Gérôme or Cabanel than Monet. Meeting Impressionists like Monet, Degas, and Renoir transformed her: she embraced plein air painting, large canvases, vivid color, and light effects.

Exhibiting with the Impressionists

Marie showed with the Impressionists three times: 4th, 5th, and 8th exhibitions (1879, 1880, 1889), standing alongside Cassatt, Morisot, and Gonzalès as one of few women in the group. Critic Gustave Geffroy named her one of “les trois grandes dames” of Impressionism with Morisot and Cassatt.

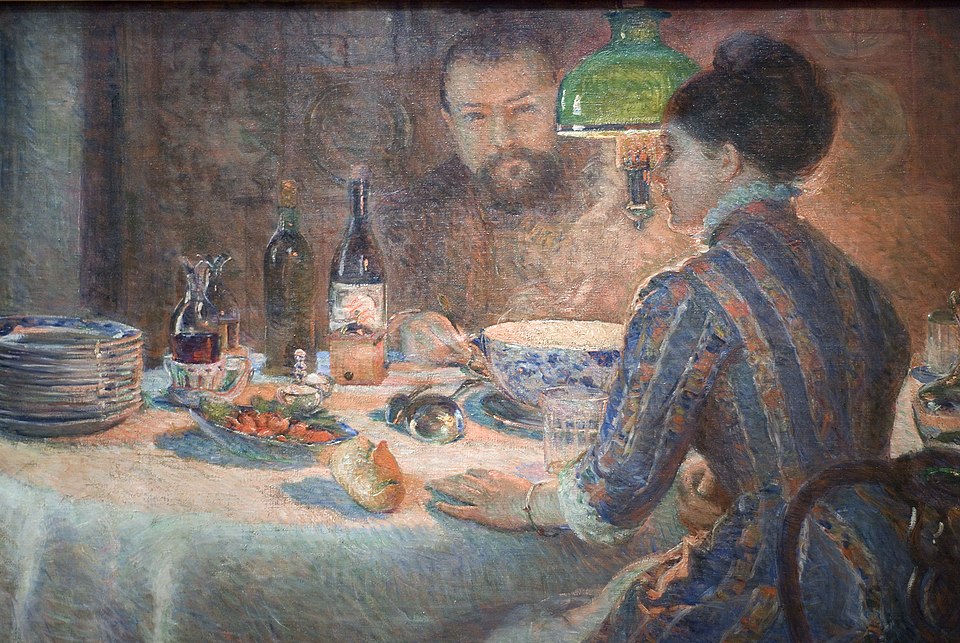

The Lady in White Masterpiece

Her paintings focused on “feminine” themes: domestic scenes, gardens, portraits she transformed through color and light experiments. Iconic “The Lady in White” uses rippling white fabric as a canvas for subtle tonal play, showcasing advanced Impressionist sensitivity.

A Jealous Husband’s Criticism

Her own husband became her fiercest Impressionism foe: he deemed the style “ugly,” critiqued her canvases, hid them from guests, and belittled her ambitions. Son Pierre recalled Félix’s toxic remarks, motherhood duties, and societal misogyny forcing Marie to abandon painting around 1890.

Disappearing from Art History Canon

She produced around 157 works in her lifetime, but only 31 located today – others lost in private collections, often unattributed. For decades mentioned mainly as Félix Bracquemond’s wife, not independent artist.

Rediscovered by Feminist Art History

From the 1970s, feminist art historians revived her legacy, calling her Impressionism’s “hidden gem.” Modern exhibitions of the four Impressionist women – Morisot, Cassatt, Gonzalès, Bracquemon – reveal how much the canon lost silencing her voice.

Dismissed as her husband’s shadow, Marie Bracquemond pioneered the transition from academicism to radical Impressionism while exhibiting with the avant-garde’s best. Her cross-medium talent, forced silence, and feminist rediscovery make her a vital symbol of women artists reclaiming their place in history.